Tampa Bay’s Not-So-Secret Weapon

In 2018, they finished with baseball’s ninth-best offense when Tommy Pham went incandescent for the last two months of the year. The best hitter on the team who made at least 400 plate appearances was C.J. Cron, and his 123 wRC+ won’t blow anyone’s socks off. In 2019, they had the 11th-best offense led by Austin Meadows with a 142 wRC+. This year, they finished with the eighth-best offense, with Brandon Lowe the headliner. Many pieces, no truly gamebreaking talents; it’s starting to feel like the Rays way.

The Rays seem to believe the hype. In the first game of the Wild Card round, Arozarena batted third in the lineup. In the second game, with the platoon advantage against Hyun Jin Ryu ???, he batted second. Tampa Bay is treating Arozarena like one of the best hitters on the team. Let’s take a quick look at how this can be the case for a player who wasn’t even in the Tampa Bay system or on any Top 100 prospect lists before this year.

As the joke goes, Tampa Bay never loses a trade. Arozarena was the main part of Tampa Bay’s return when they traded Matthew Liberatore to the Cardinals in the offseason, and at the time, I theorized that they must have seen him as a long-term starter and undervalued asset. They can’t always be right, though, and many neutral observers thought that this trade might be a rare loss for them.

Arozarena had the start of his season delayed for undisclosed reasons, and spent a month at the team’s alternate site getting up to speed. He joined the team on August 30, ostensibly mainly to bat against lefties, and proceeded to hit everyone, regardless of handedness, for the remainder of the season.

Coming into the year, there was reason to question Arozarena’s power. He hit only five homers in a 311 PA stint with Triple-A Memphis in 2018, and while he managed 12 in a similar sample in 2019, that was the year that the major league ball went to Triple-A and turned the PCL into home run heaven. Arozarena doesn’t have the frame you’d expect for a thumper, and he hits a lot of grounders; it’s not exactly a traditional power hitter profile.

This year, Arozarena has made those concerns look silly. He clobbered seven homers in his month in the majors, good for a top 10 ISO mark in all of baseball. Statcast’s batted ball tracking backed it up; he barreled up 14% of the balls he put into play, the same mark as literally Joey Gallo on the season. 44.2% of his batted balls left his bat above 95 mph, and he also got the ball off the ground more often; his 46.5% groundball rate, while still high, was more “slightly elevated” than peak Eric Hosmer.

Watch him bat, and you’ll be astounded how much power he generates. His leg kick, if it can even be called that, is more of a timing mechanism than anything else, and his whole body remains quiet, to my eyes, throughout the swing:

That’s a pretty clean way to hit a baseball nearly 400 feet the opposite way — Statcast estimated it at 394. It’s one of three homers he hit to the right side of the field. Pitch him in, and he’s capable of keeping his hands in and pulling the ball, as he did here on his hardest-struck ball of the year:

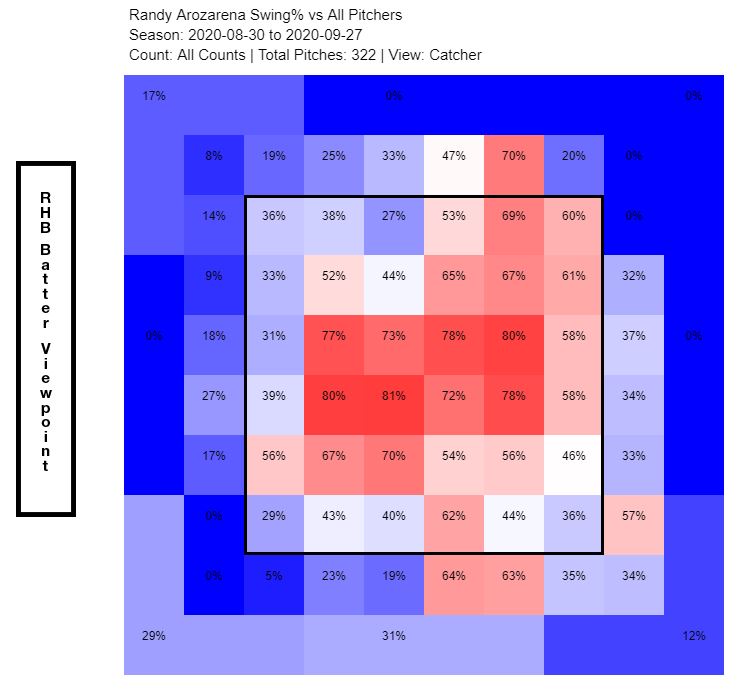

With that swing, Arozarena can’t rely on golfing low balls high enough to generate extra base power. He relies on swinging at the right pitches, and he’s been nothing short of excellent on that front this year:

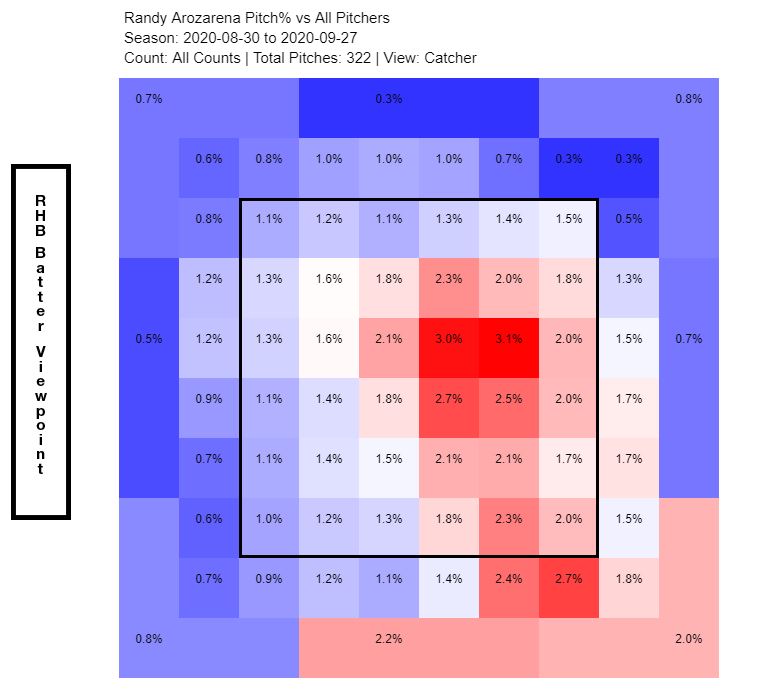

This map shows how often he swings in each region of the plate, and it’s exactly what you want to see from someone with Arozarena’s swing plane. He’s generally good about avoiding the bottom of the strike zone, where grounders live. He also seems to be adapting to what he sees. You might notice that he’s willing to swing at pitches away, both high and low. That’s likely because pitchers are completely avoiding the inside part of the plate against him this year:

In fact, there’s essentially nothing to quarrel with when it comes to Arozarena’s production on contact this year. His xwOBACON — mmm, delicious bacon — a statistic that uses launch angle and exit velocity of batted balls to approximate production, is in the 92nd percentile among all hitters, a smidge ahead of fellow Cuban rookie Luis Robert, who has deservedly drawn Rookie of the Year consideration for his all-fields power.

That doesn’t mean he’s going to keep hitting a home run once every 11 plate appearances; he isn’t peak Barry Bonds. It does mean, however, that he’s doing all the things that make hitters succeed: hitting the ball hard, and getting it in the air often enough to turn that hard contact into doubles and dingers.

If there’s something to nitpick in Arozarena’s 2020 — and honestly, I’m not sure there is — it’s a ballooning strikeout rate without a matching rise in walks. Arozarena swung and missed at 14.9% of the pitches he saw this year, by far a career high. He displayed customary patience outside the strike zone, chasing only 26.8% of the time, but simply made a lot less contact than in his career before this year when he did swing.

That’s not a terrible thing on pitches outside the strike zone, because contact on a bad pitch — generally a breaking ball below the zone — isn’t likely to result in the kind of results Arozarena is looking for. It does, however, suggest a susceptibility to breaking stuff in the zone; he whiffed on 45.5% of the breaking pitches he swung at this year, and five of the 17 he swung at in the strike zone.

In an absolutely minuscule postseason sample, he hasn’t had any trouble hitting bendy stuff. All three of his whiffs have been on fastballs, and when he faced Ryu, he tattooed an in-zone curveball for a double:

The Yankees are well-equipped to attack Arozarena’s weak points. Adam Ottavino is tailor-made to attack him; he’s a righty who can fill the zone with sliders. Masahiro Tanaka is much the same; he has a wide array of secondary pitches and no desire to challenge someone with a fastball and lose. Gerrit Cole is Gerrit Cole.

The Rays could pivot away from Arozarena against tough righties; they can roll out an outfield of Meadows, Kevin Kiermaier, and Brett Phillips if they want to overload on lefties. They’re certainly not above benching players who are performing well if they think it will give them an advantage.

At the moment, however, I don’t think they will. The Rays might have built a reputation for mixing and matching in the past few years, but to me, that’s simply an artifact of the hand they’ve been dealt. Tampa Bay isn’t about being cute for cuteness’s sake; the point of the whole exercise is to win baseball games as efficiently as possible.

In the past few years, that meant hiding the weaknesses of one-note hitters. In these playoffs, however, it’s hard to imagine how optimal behavior could mean anything other than letting your white-hot, precocious outfielder play as much as possible. The Rays will need to squeeze out all the juice they can from their lineup to beat the Yankees. Right now, it looks like a lot of that juice comes from playing Arozarena every day and waiting for the extra-base hits to roll in.