Orlando Arcia Snatches Defeat From the Jaws of Victory

Things don’t always work out so cleanly, and 2020 had a way of ruining everything. Urias contracted COVID-19 in July and didn’t debut until August 10. The third base situation didn’t quite work out; Brock Holt and Eric Sogard struggled, and Jedd Gyorko played mainly first base — the addition of the universal DH meant that their brief Ryan Braun experiment at first never amounted to much.

Well, no, you can’t. Here’s a list of Brewers sorted by the percentage of their plate appearances that came with runners on base:

| Player | PA | Runners On | Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jacob Nottingham | 54 | 27 | 50.0% |

| Orlando Arcia | 189 | 86 | 45.5% |

| Ryan Braun | 141 | 64 | 45.4% |

| Eric Sogard | 128 | 57 | 44.5% |

| Jedd Gyorko | 135 | 60 | 44.4% |

| Keston Hiura | 246 | 106 | 43.1% |

| Daniel Vogelbach | 67 | 28 | 41.8% |

| Luis Urias | 120 | 50 | 41.7% |

| Jace Peterson | 61 | 24 | 39.3% |

| Ben Gamel | 127 | 49 | 38.6% |

| Christian Yelich | 247 | 93 | 37.7% |

| Justin Smoak | 126 | 46 | 36.5% |

| Omar Narvaez | 126 | 45 | 35.7% |

| Avisail Garcia | 207 | 71 | 34.3% |

You hate to see it — the Brewers’ weakest projected hitter was coming up in big spots with regularity. Good news — Arcia put up a career-low strikeout rate, career-high slugging percentage, and a 96 wRC+, nearly league average after years in the wilderness. Surely, the Brewers profited from having their ex-ante worst hitter turn from a pumpkin back into a carriage, right?

Well, no, they didn’t. Arcia led the major leagues in a counting stat. The only downside: it was grounding into double plays. His 10 tied for the league high with three hitters who came to the plate significantly more often: Jose Abreu, Anthony Rendon, and Evan Longoria. Let’s take a deep(ish) dive into the world of double plays and the kinds of batters who hit into them.

First things first: you can only hit into a double play if you come to the plate in a double play situation. That’s a tautology, but it doesn’t make it less true. Rather than just focus on Arcia’s 10 double plays, consider instead the percentage of the time that he got doubled up when he had a chance at it — with a runner on first base and less than two outs. For context, the league average comes in a hair under 10%:

| Player | Opportunities | GIDP | Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Orlando Arcia | 33 | 10 | 30.3% |

| Evan Longoria | 43 | 10 | 23.3% |

| Jonathan Schoop | 37 | 8 | 21.6% |

| Colin Moran | 43 | 9 | 20.9% |

| Jose Abreu | 53 | 10 | 18.9% |

| Anthony Rendon | 53 | 10 | 18.9% |

| Ryan Braun | 32 | 6 | 18.8% |

| Gary Sanchez | 32 | 6 | 18.8% |

| Travis d’Arnaud | 43 | 8 | 18.6% |

| Yadier Molina | 38 | 7 | 18.4% |

It’s not my bit, but you know the thing where the gap between first and second is the same as the gap between second and some much higher place? Arcia was roughly as far ahead of Longoria as Longoria was ahead of Erik Gonzalez, 19th in baseball at 16.1%.

Quickly before we move on: Arcia was one of the worst hitters of the Statcast era when it comes to grounding into double plays. I’m planning on using sprint speed data later in this article, so we’ll stop it at 2015, but here’s the leaderboard since 2015, minimum 30 double play opportunities:

| Player | Year | Opportunities | GIDP | Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Casey McGehee | 2015 | 55 | 18 | 32.7% |

| Eric Campbell | 2015 | 35 | 11 | 31.4% |

| Orlando Arcia | 2020 | 33 | 10 | 30.3% |

| Yonder Alonso | 2019 | 44 | 13 | 29.5% |

| Christian Bethancourt | 2016 | 31 | 9 | 29.0% |

| Ben Revere | 2016 | 42 | 12 | 28.6% |

| Joey Butler | 2015 | 56 | 16 | 28.6% |

| Mike Aviles | 2015 | 63 | 18 | 28.6% |

| Chris Johnson | 2016 | 47 | 13 | 27.7% |

| Miguel Rojas | 2016 | 37 | 10 | 27.0% |

You may not remember McGehee, but he’s a big beefy boy; a corner infielder who was hardly fleet of foot. Revere aside, there are a lot of slow-footed hitters on this list, a quality that certainly doesn’t apply to Arcia. That led me to my first question: what can sprint speed tell us about a player’s propensity to hit into a twin killing?

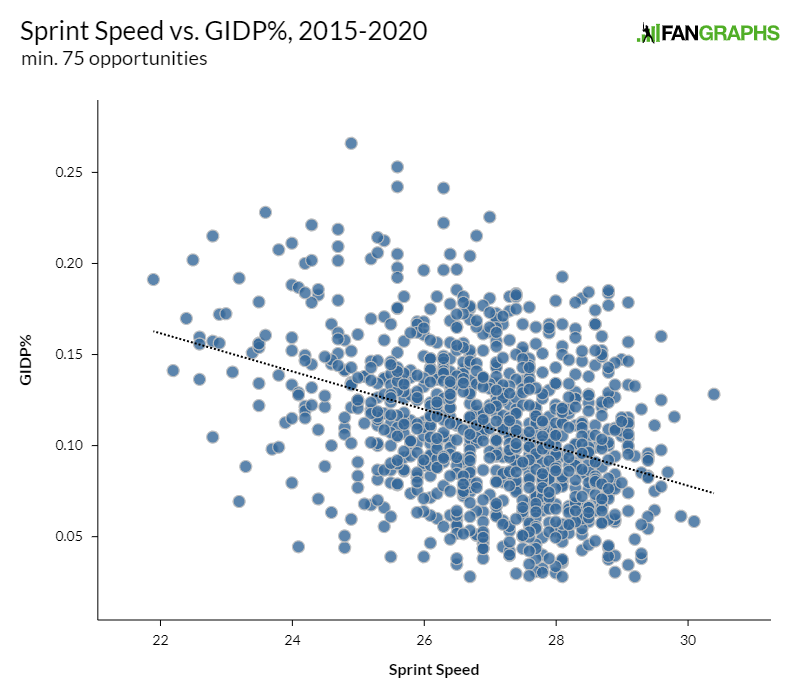

To answer that question, I took every player-season with at least 75 double play opportunities since 2015 and looked at two things: that player’s speed and the rate at which they hit into double plays. How’s the relationship? It’s present but faint:

That explains some of Arcia’s troubles. He’s slower than you’d expect for a shortstop; his 26.2 ft/sec sprint speed was below league average in 2020, and he hasn’t cracked 27 ft/sec since 2018. He’s hardly molasses out there, however; there’s obviously a lot more at work here.

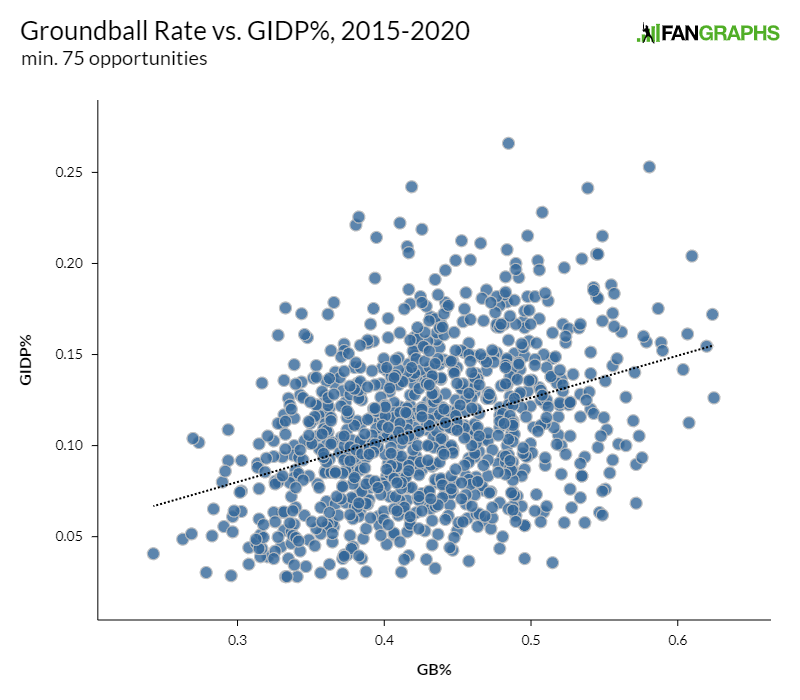

What about groundball rate? You can’t ground into a double play if you don’t hit a grounder. Arcia hits plenty of them; 46.1% of his batted balls in 2020 were grounders. Time for another graph; this one of groundball rate against double play rate:

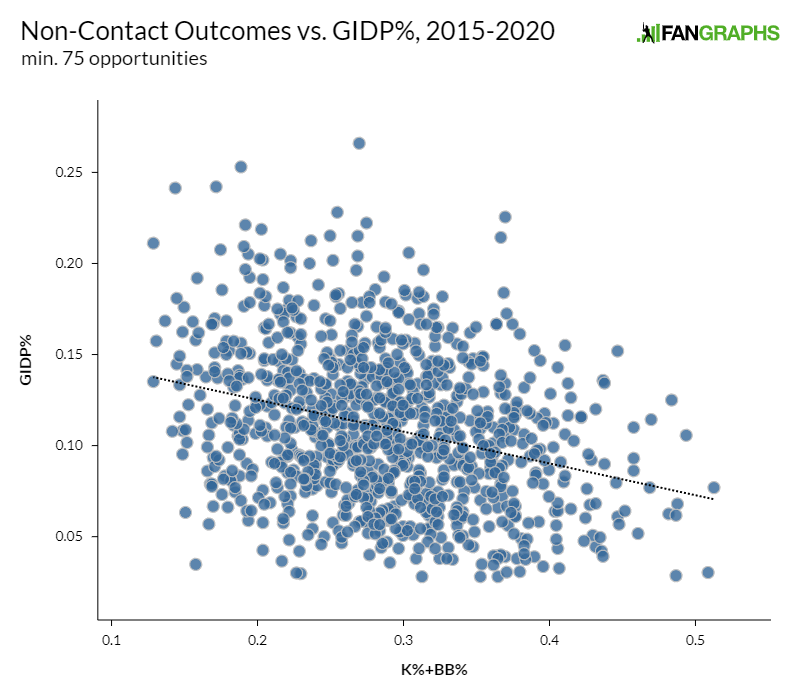

Yet again, that’s decent but not great. If you’re into vague nods towards statistics, both of them carry an r-squared value below 0.15. Let’s keep going. What about strikeout rate and walk rate? The less often you do one of those two, the more frequently you put the ball in play, which means more chances for grounders and more double plays. Yet again, eh:

It’s time to pull out one last trick, one I considered a few years ago in pondering double plays. The harder you hit the ball on the ground, the more time fielders have to convert it into two outs. In 2018, for example, Hanley Ramirez hit his average grounder at a preposterous 94.6 mph. In 2020, Shogo Akiyama hit his average grounder at 80.7 mph. In a roughly equal number of plate appearances, Ramirez hit into nine double plays, while Akiyama hit into only one. I’ll save you a graph on this one — it’s the weakest of the four factors we’ve tried so far. We’re really reaching at this point.

Arcia did hit the crap out of his grounders in 2020, but it’s unclear how much that matters. From here, I’m going to do something that serious statisticians would call “playing with your food” or “not real math.” We’re going to use a multiple linear regression and come up with some kind of silly prediction for how many double plays Arcia would have grounded into if these factors could perfectly predict the outcome.

Throwing all the variables into a blender, you get some silly (and very likely wrong!) formula with an adjusted r-squared of 0.34, which means (very loosely, using plain English in an attempt to describe it, please don’t turn this article in for a statistics test, etc.) that a third of the variation in GIDP rate can be explained by variation in our four factors. It also unsatisfyingly predicts that Arcia should have had a 13% GIDP rate in 2020, not his actual 30.3%.

What gives? Well, using stupid regressions and asking why they don’t mimic reality is no way to go through life. Any number of things — a missing key explanatory stat, something in Arcia’s game that changes with runners on base, sheer statistical noise — could be wrong. Arcia wasn’t some hard-luck victim, though; he’s in the top 10% when it comes to predicted GIDP%.

Arcia is slower afoot than average, puts the ball in play more often than average, hits it on the ground when he does, and hits his grounders hard. It’s a cocktail designed for failure. It’s not nearly enough to explain everything, though. Sometimes the best-laid plans go sour. Sometimes your roped double finds a glove and turns into a helmet slam:

That’s just baseball. Numbers might generally help make sense of the sport, but they come nowhere near painting a perfect picture. Before 2020, Arcia was a terrible hitter who hit into double plays at a roughly average rate. This year, he set a new high in wRC+ — and got doubled up at nearly triple his previous rate.

Which one matters more? It depends on what you mean. This year, the double plays were backbreaking. Ask the Brewers, though, and I’m sure they’d take the tradeoff. Before 2020, ZiPS projected Arcia for a .669 OPS in 2021. After a year of good hitting and horrible double plays, it projects him at .685. Steamer is even more optimistic, checking in at .720. Arcia might have cost the Brewers a ton of outs this year with the bat, but what he did at the plate in 2020 is a positive sign anyway.