I can’t confirm that this is true — sadly, Statcast doesn’t track “balls lost in the light.” But so far this season, it’s seemed to me like more catchable fly balls have disappeared into the sky than is usual for a 30-day period of major league baseball. Surveying the range of fly balls and popups with an xBA of less than .100 that didn’t result in outs, the earliest lost ball I can find is from July 27, when the Blue Jays’ Derek Fisher sent a fly ball into the right-field sunshine. Adam Eaton thought he could see it. Victor Robles, from his vantage point in center, knew that he couldn’t. And as Robles desperately sprinted over, Eaton tried even more desperately to correct his positioning. He leaped backward, the ball spinning away off his glove. His recovery attempt had only made things worse.

The next day, in the evening shadows of Cincinnati, Shogo Akiyama, standing in the sun and trying to shield his eyes, completely lost track of a fly ball off the bat of Jason Kipnis.

On August 14, in the top of the second, Roman Quinn of the Phillies watched a ball drop in front of him — though both he and Harper had run forward, neither of them was in a position to actually catch it. A run scored on the play. An inning later, in the top of the third, a similar fly ball was hit, this time catchable for Quinn in center — a chance to make up for the missed play in the previous inning. He ran in, ready to catch it. But Quinn didn’t see the ball until it was too late, until it was dropping in behind him, and what could have been the third out instead became a runner on base.

Those are just a few. They get me every time, though. These plays always look funny — that GIF of the ball falling behind an expectant Jayson Werth is one of my favorites. But part of the reason why they’re so funny is there’s something about these plays that’s instantly, painfully recognizable. Anyone who’s played baseball or softball has probably lost a fly ball in the light at some point, whether it’s the artificial white of stadium lights on a dark sky or the overpowering brightness of the afternoon sun. It’s a terrible feeling, not least because it takes so goddamn long for the play to unfold. If you mishandle a short-hop, at least the ball is coming at you fast. At least it probably isn’t too far away from you. But when you lose a ball in the light, the time between when you hear it leave the bat and when you hear it hit the ground is a minor eternity. You’re suspended in a moment of utter helplessness. The ball could be immediately above you, a second away from bouncing off your forehead, and there would still be nothing you can do.

Losing a ball in the light isn’t an error. It’s not a lapse of skill or judgment. It isn’t really preventable; it can’t be improved by running drills or working on one’s defense. But it has the same result as an error, and in a way, it can be almost worse than one: It still feels like a failure on your part, even though there was nothing you could have done. That feeling, equal parts helplessness and guilt, has become all too familiar. Maybe there haven’t been more balls lost in the light this season — maybe each of them has just resonated with me more.

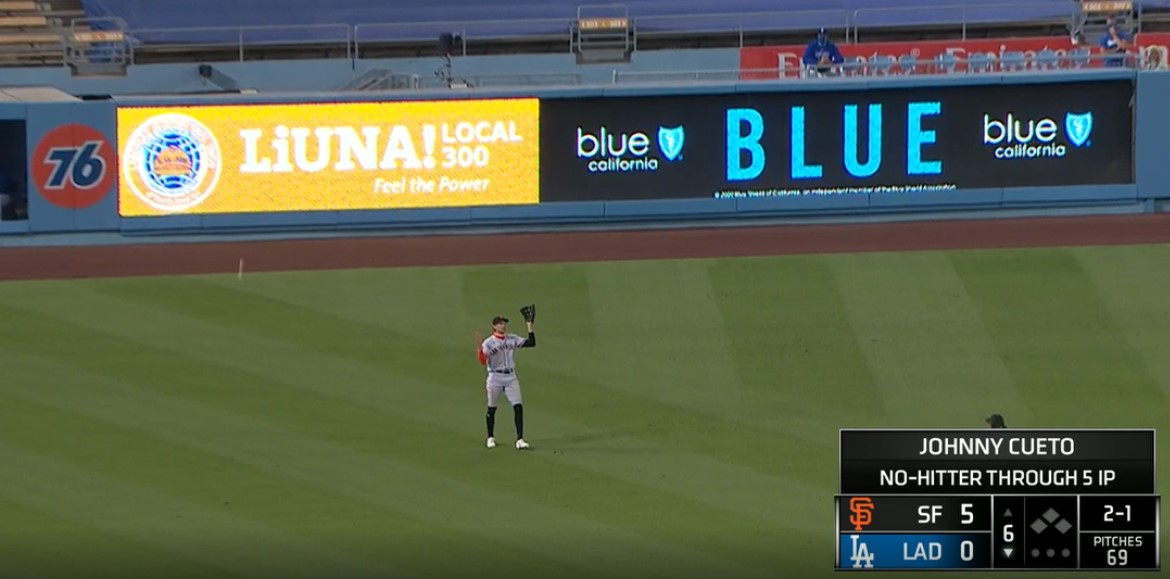

So of all the many, many chaotic things that have happened over the single month of major league baseball we’ve watched this year, there’s one image that has returned to my mind far more than any other. Let me bring you back to the night of August 8th: Dodger Stadium in the bottom of the sixth. Johnny Cueto had still not allowed a hit. On a 2-1 count, Enrique Hernandez sent a high fly ball to left. Hunter Pence dutifully trotted over, waving off assistance, and stood waiting for the ball to fall into his glove.

It’s hard to pinpoint exactly when Pence realized he couldn’t see the ball. But there is one moment that stands out on the broadcast: He drops his right arm, and, for a split second, looks straight ahead — maybe at Mauricio Dubón, who was not looking directly upward into to the lights, and may have been warning him of the impending disaster; maybe he thought the ball had already landed ahead of him. Clearly, he realizes that something is wrong. Then he looks back up, his right arm now raised with his palm extended outward in the sad, universal gesture of “I don’t know!”

Dubón sprints helplessly into frame, the ball hits the ground, heavy and untouched, around 20 feet behind where Pence had positioned himself. Maybe he never saw it at all. And even though the damage had already been done, and even though Mike Yastrzemski was flying over from center to field the ball, a last-ditch effort to prevent Hernandez from making it all the way around the bases — Pence turned around and ran. It wasn’t a full-pace run; there was nothing he could do. But he ran, nonetheless, only stopping when Yastrzemski had picked the ball up and whipped it to third. Then he just stood there, defeated. After the game, he said he felt absolutely awful.

I keep thinking about Pence, standing there alone on the wide, wide grass sea, looking to the sky for something he knew was there but couldn’t see. It didn’t matter how many fly balls he’d fielded successfully in his life, or how unlikely it was that a ball hit at that launch angle with that exit velocity would land for a hit. When a ball gets lost in the lights, there’s nothing you can do but hold out your hands and wait.

Read More