Yesterday, Marcus Stroman accepted the Mets’ qualifying offer, returning to the team on a one-year deal worth $18.9 million. Later in the day, Kevin Gausman accepted his own qualifying offer, making them the only two players to accept their QOs this year. Gausman reportedly had multi-year offers in hand but chose to stay with the Giants anyway, taking the guaranteed $18.9 million salary over any long-term security a multi-year contract would provide. It’s not a surprising decision on Gausman’s part, especially since he and the Giants have made some progress on negotiating an extension already.

Stroman’s decision to accept the QO wasn’t exactly a surprise either. The Mets traded for him a year earlier than expected, in July of 2019, when he still had a year and a half of club control remaining. He pitched well enough down the stretch last year, but the Mets were already looking forward to 2020 when they acquired him. Unfortunately, a calf injury sustained towards the end of summer camp sidelined him to start this season, and he eventually decided to opt out of the entire campaign in early August. Because he didn’t pitch in 2020, he would have entered the free agent market at a serious disadvantage. Taking the QO defers some of that risk since he’ll be a free agent again after the 2021 season, but the hope is that he’ll have another full year of innings under his belt at that point.

For the Mets, this was their first major move since Steve Cohen finalized his purchase of the team. Stroman’s QO was offered by the outgoing executive vice president and general manager Brodie Van Wagenen before he was dismissed by Cohen, making for a potentially awkward situation. But in his announcement, Stroman voiced great enthusiasm for Cohen and the winning culture he laid out in his first press conference as owner.

After watching the presser, I’m beyond excited to play for you sir. I could feel the excitement and passion you’re going to bring daily. Let’s go be great! @StevenACohen2

— Marcus Stroman (@STR0) November 11, 2020

The eagerness Stroman expressed in his tweet mirrors the optimism that has spread throughout the Mets fan base since Cohen took over. His $18.9 million salary in 2021 is likely higher than what he would have gotten on the open market, so the Mets are paying a slight premium on his services. But Cohen has already expressed a desire to open up the payroll when the time is right. Stroman’s salary isn’t a concern long-term, but it could affect their willingness to spend any additional dollars in free agency, especially coming off this abnormal season.

Beyond any payroll implications, one of the recurring concerns during Stroman’s time in New York has been the quality of the Mets’ infield defense. Since his debut in 2014, Stroman’s 58.7% groundball rate is the third highest among all qualified starters. His pitch arsenal has its foundation in a diving sinker, and all of his secondary pitches generate groundball contact at a rate higher than average for their respective pitch types. In 2019, the Mets’ defense as a team was atrocious. Their overall defensive efficiency (.696) and their efficiency in converting groundballs into outs (.753) were both third-worst in the NL. They were second-to-last in the NL in team UZR (-12.8) and dead last in team DRS (-86).

After Stroman joined the Mets in late July of that year, his BABIP increased by 44 points, up to .337. His groundball rate dropped by eight points, so an increase in groundball hits wasn’t the only problem he dealt with in Queens. His home run rate also shot up, but without any corresponding rises in hard hit rate, barrel rate, or exit velocity, it’s likely all those home runs were just an artifact of small sample bad luck.

Even though Stroman didn’t pitch in 2020, it’s worth checking on the Mets’ defensive performance this season to see if it affects his outlook for 2021. On the surface, it doesn’t look like much has changed. As a team, their defensive efficiency dropped to .684, and on groundballs, they fared a hair worse than last year as their efficiency dropped to .751. Both marks were the second-worst in the NL. But the advanced defensive metrics tell a different story, sort of. Here’s how UZR, DRS, and Baseball Savant’s Outs Above Average graded out their infield over the last two seasons.

| Year | 2B/SS/3B UZR | Rank | 2B/SS/3B DRS | Rank | 2B/SS/3B OAA | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | -0.9 | 16 | -27 | 26 | -12 | 23 |

| 2020 | 3.9 | 7 | -14 | 28 | 10 | 3 |

Last year, each of the advanced defensive metrics saw the Mets infield as middling at best (UZR) but more likely one of the poorest defenses in baseball (DRS, OAA). There are plenty of questions about the efficacy of these metrics in a shortened season, but two of them indicate some improvement on the part of the Mets infielders. OAA in particular was rather bullish about their ability to create outs this year, ranking them third in all of baseball behind the Padres and Cleveland.

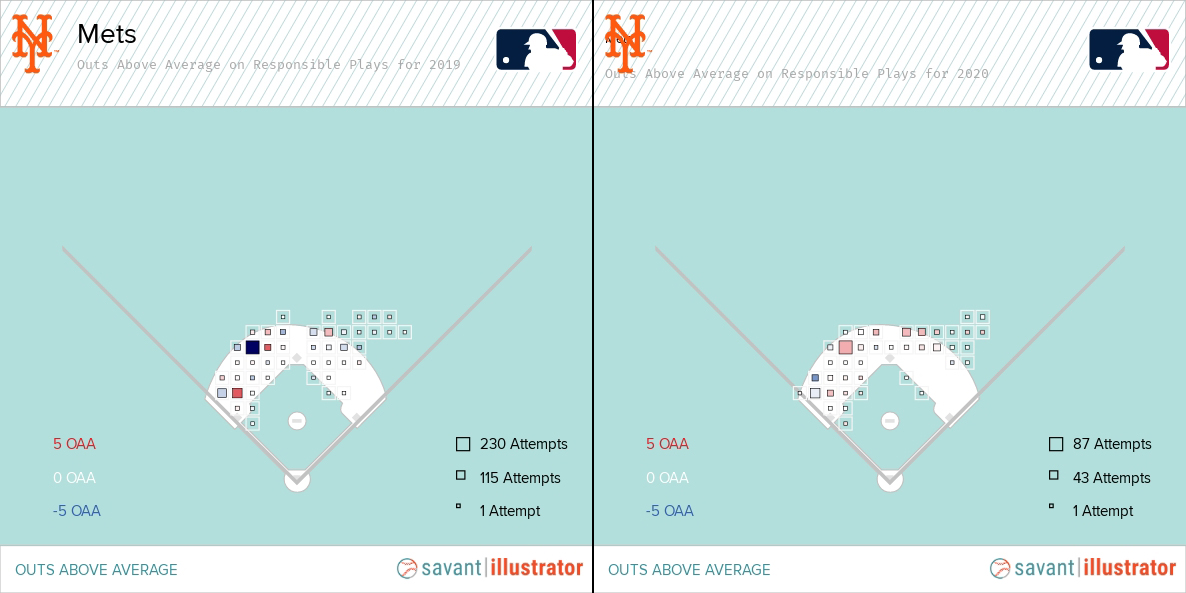

It’s hard to gauge the accuracy of metrics like DRS and UZR since they’re both a bit of a black box when it comes to inputs, assumptions, and how they handle things like positioning. OAA is far more transparent about how it calculates it’s final metric and it’s granularity is a benefit when there’s a small sample to work with. Here’s a visual showing their Outs Above Average based on the infielder’s starting position in 2019 and in 2020.

You can see the improvement in the number of red squares on the right in the place of where a blue square was on the left. The biggest difference was in the performance of their shortstops. Amed Rosario improved from -8 OAA in 2019 to +2 in 2020, and the newcomer Andrés Giménez provided elite defense (+5 OAA) in his limited innings at short. The team’s defense at second base also improved with Robinson Canó going from -2 OAA to +2 and Luis Guillorme adding +2 in limited innings as well. And because OAA is a cumulative stat, those marks in 2020 could possibly represent even better improvement if we hypothetically extrapolated across a full season.

Another thing the visual above shows us is that the Mets aren’t very creative when it comes to positioning their infielders. In 2019, they shifted their infield just 14.1% of the time, the third-fewest infield shifts in baseball. They were a little more shifty in 2020, increasing their rate by seven points up to 21.4%. But that still placed them in the bottom tier in baseball. That refusal to reposition their infielders could explain why their defensive efficiency on groundballs didn’t really budge from 2019 to 2020 while their individual defensive ratings improved. Their infielders were able to convert balls hit to them into outs at a higher rate, but their inefficient positioning meant there were just as many balls hit into the holes in their defense.

With Rosario and Giménez looking like they’ll split time at shortstop in 2021 and Canó and Guillorme holding down the keystone, the Mets defense up the middle looks solid if they can hold onto the improvements they saw in 2020. Third base is a bit of a mystery. J.D. Davis was a pretty significant hindrance defensively (-5 OAA). If the NL uses the designated hitter again in 2021, then the Mets can move Davis to DH or left field while Jeff McNeil takes reps at third. If there isn’t a DH in 2021, they’ll have two defensively challenged hitters — Davis and Dominic Smith — to fit into the lineup alongside McNeil.

The return of Stroman also solidifies the Mets starting rotation. Jacob deGrom and David Peterson were likely the only two starters who were guaranteed a spot in 2021. Noah Syndergaard will be recovering from Tommy John surgery and Seth Lugo and Steven Matz are in a bit of a limbo — Lugo could return to the bullpen and Matz could be designated for assignment. Stroman gives the Mets a mid-rotation arm they would have been seeking anyway, and their defensive improvement should quell the concerns about his batted ball profile.

Read More